Real-World Context: Why This Still Confuses Teams

Most Android developers know this statement by heart:

“Google Play requires Android App Bundles (AAB). APK is a legacy.”

But in real projects—especially Flutter, React Native, and apps with native .so files—this transition creates confusion during:

- Crash debugging

- Play Store delivery issues

- ABI / density mismatches

- Android 15 (16 KB page size) compatibility checks

If you’ve ever asked:

- “Why does my locally tested APK work but the Play Store build crashes?”

- “Where did my APK go after uploading AAB?”

- “Why is Play generating multiple APKs?”

This blog answers what actually changes internally—from a production engineer’s lens.

APK vs AAB: High-Level Difference (Quick Recap)

Now let’s go under the hood.

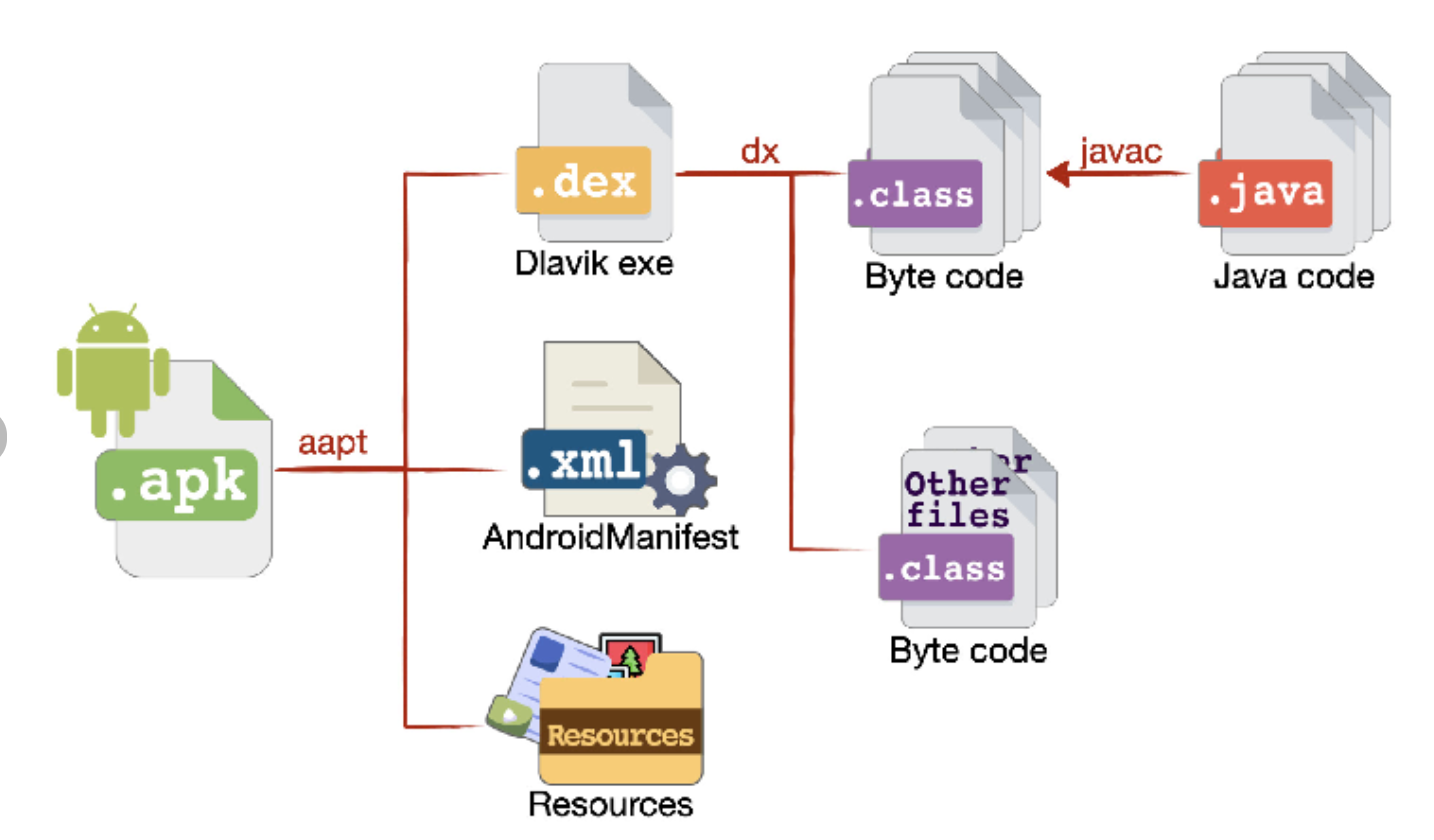

An APK (Android Package Kit) is a single, self-contained file that includes all app resources and binaries in one bundle. This means it ships with every supported ABI, screen density, and language, regardless of the device it’s installed on.

Internally, an APK contains:

- Compiled app code (classes.dex)

- All native libraries (lib/armeabi-v7a, arm64-v8a, x86, etc.)

- Resources for all screen densities and locales

- Assets and the Android manifest

Because everything is packaged together:

- The file size is larger

- Devices download unused resources

- Updates often require re-downloading the entire APK

APKs are simple to distribute and install manually, but they’re less optimized for modern Play Store delivery, especially for large apps and multi-architecture support.

An APK is a fully packaged, install-ready artifact.

myApp.apk

├── classes.dex

├── lib/

│ ├── arm64-v8a/

│ ├── armeabi-v7a/

│ ├── x86/

├── res/

├── assets/

├── AndroidManifest.xml

Key Characteristic of APK

- Contains all ABIs: Every CPU architecture (ARM, ARM64, x86, etc.) is bundled, even though a device uses only one.

- Contains all screen densities: Resources for all screen sizes and DPIs are included, regardless of the target device.

- Contains all locales: All language and regional resources ship in the same package.

- Same APK installs on every device: One universal APK works across all Android devices without device-specific optimization.

Why APK Worked Well Historically

- Simple distribution: A single file was easy to host, share, and distribute.

- Easy sideloading: APKs could be installed directly without Play Store involvement.

- Predictable crash reproduction: Since everyone used the same binary, debugging issues was straightforward.

Why APK Became a Problem

- Huge app size: Bundling everything significantly increased download size.

- Wasted storage: Devices stored many unused resources and libraries.

- Unused native libraries: Multiple .so files existed for architectures that never ran.

- Slower installs on low-end devices: Larger APKs meant longer install times and higher resource usage.

AAB – Modular & Deferred Packaging

An Android App Bundle (AAB) is a publishing format, not a directly installable app. Instead of shipping everything to every device, it allows Google Play to generate optimized, device-specific APKs at install time.

Key Characteristics of AAB

- Split by ABI: Native libraries are separated by CPU architecture, so devices receive only what they need.

- Split by screen density: Only the required drawable and layout resources are delivered.

- Split by locale: Language resources are downloaded based on the user’s device settings.

- Dynamic feature modules: Optional features can be downloaded on demand instead of at install time.

Why AAB Is Better for Modern Apps

- Smaller install size: Users download only device-specific resources.

- Faster installs: Reduced package size improves install time, especially on low-end devices.

- Lower storage usage: No unused libraries or resources are stored on the device.

- Play Store optimization: Google Play handles splitting, signing, and delivery automatically.

Trade-Offs of AAB

- Not directly installable: Requires Google Play to generate APKs.

- Harder manual testing: Device-specific APKs can complicate crash reproduction.

- Limited sideloading: Manual installs require bundletool or Play-generated APK

AAB – Modular & Deferred Packaging

An Android App Bundle (AAB) is not installable.

It is a publishing format, not a runtime artifact.

Internal layout:

app.aab

├── base/

│ ├── manifest/

│ ├── dex/

│ ├── res/

├── feature1/

├── feature2/

├── BUNDLE-METADATA/

What Happens After Uploading AAB

Once uploaded to Google Play:

- Play analyzes device specs

- Generates Split APKs

- Delivers only required pieces

Example generated artifacts:

base.apk

config.arm64_v8a.apk

config.xxhdpi.apk

config.en.apk

The Key Internal Shift: You No Longer Control the Final APK

This is the most important mental shift.

What Changes for Native Libraries (.so)

This is where real production issues appear.

APK World

- Every .so ships together

- Even broken ABI libs stay hidden if unused

AAB World

- Only one ABI is delivered

- If any ABI is broken, that device crashes at launch

arm64-v8a → OK

armeabi-v7a → misaligned

Debugging Becomes Harder (But Smarter)

APK Debugging

- Install one file

- Reproduce easily

AAB Debugging

- You must extract split APKs:

bundletool build-apks \

--bundle=app.aab \

--output=app.apks \

--mode=universalLesson from production:

Always test APKs generated by Google Play, not just local builds. Play Store builds can differ due to app bundling, optimization, and device-specific splits.Testing them helps catch issues that may not appear in local APKs.

Best Practices (From Real Apps)

Always validate the AAB output, not just your local builds. Google Play processes and optimizes AABs differently for each device. Validating the final output helps prevent unexpected runtime issues.

bundletool validate --bundle app.aab

References:

Conclusion:

APK vs AAB is more than a format change it’s a change in control. With AAB, you no longer ship the final APK; Google Play generates it per device. This affects native libraries, crash behavior, and debugging.

If your app works as a local APK, that’s not enough. Always validate and test Play-generated APKs, especially for ABI-specific issues. Once you treat AAB as the source of truth, Android delivery becomes predictable and stable.